The Hidden Seasonal Cycles of the Kawartha Lakes

By KLT Volunteer, Joseph Gentile

The winter season has officially settled into the Kawarthas and many of you are probably getting out your skis and snowshoes for a whimsical day out in the snow. But, there remains an important winter process that is hidden under all the snow and ice that human eyes cannot physically see. Maybe you have wondered: Why doesn’t the entire lake freeze solid in the winter, what happens to aquatic life when the water freezes, or why do certain lakes freeze and thaw quicker than others? The answer to these commonly asked questions involve the peculiar physical properties of water.

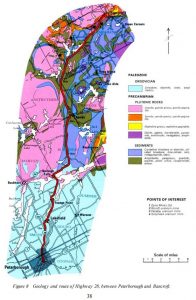

The Kawartha Lakes region is a geological gem that many geologists have visited and fallen in love with. The geography of the Kawarthas can be divided into its northern and southern halves. On the northern side lies the Canadian Shield where small lakes are perched atop dense layers of weather-resistant granite and marble.

From the lookout at the Kawartha Land Trust’s Jeffrey-Cowan Forest Preserve, you can spot the rugged terrain and steep cliff faces that often border these lakes. To the south are many larger and calmer lakes that are underlain by soft and erodible limestone. This type of geologic setting can be seen along the shoreline of John Earle Chase Memorial Park and Big (Boyd/Chiminis) Island properties on Pigeon Lake.

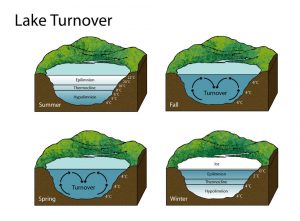

One fascinating and important characteristic of water is that it is densest at a temperature of 4°C. This property may at first seem unremarkable but, when applied to the concept of an inland lake, it allows us to explain why only the surface of a water body freezes in the winter.

In our North American climate, the temperature of inland lakes will vary at different depths. In the summer, the uppermost layer of water will be the warmest and will float on top of the cooler, denser water below. Once the colder autumn weather arrives and the upper part of the water cools to a temperature below 4°, the surface water will become denser than the water underneath and so the denser water will start to sink. This phenomenon is what we call autumn turnover. Since water is at its densest when it is in a liquid state, less dense ice is able to form on the top of the lake while the coldest densest water will sink to the bottom where it will be safe from freezing. When the weather begins to warm again in the spring, lakes will experience a spring turnover. The autumn and spring turnovers are a vital part of lake ecology that ensures that nutrients and oxygen are transported to all areas of the lake.

The yearly cycles experienced by lakes are critical to maintain the balance of nutrients and oxygen in the water and safeguard the life within the lake. The spectacular winter ice that we enjoy here in the Kawarthas is a product of these cycles. Learning about the important processes that occur under the water can show us just how alive and delicate these aquatic ecosystems are and teach us to appreciate them a little more.

So get out there and explore the pristine beauty of the Kawartha Lakes this winter! Be sure to check out, and be inspired by, the winter landscape at one of the Kawartha Land Trust’s protected properties. Having trouble picking out a spot for your next hike? Click here to browse through our properties and see the amenities included at each one. Happy hiking!

Posted February 14, 2019.